|

Midnights I READ two books about Wellfleet this

summer. One was dreadful, full of gratuitous horror and violence,

and tedious name-dropping: a comic book without pictures for

readers who cared about boating jargon and the labels on gin

bottles. The other book was Alec Wilkinson's Midnights. It was

a sheer delight. I finished it in a pleasant frame of mind, happy

that someone who wrote so well and was so entertainingly humorous,

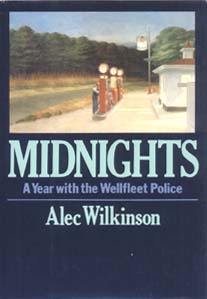

and pleasant and gentle, had found a major-league The dust jacket of Midnights carries a full-color reproduction of Edward Hopper's painting, "Gas," done in 1940, of a a Mobil station with a sign and three old-fashioned pumps -- probably one on Route 6 in the Truro-Wellfleet area -- and most likely the site of the abandoned gas station where Alec and I met for the interview. Alec described the spot and said he'd be there. I should look for an old blue Mercury Bobcat. He'd then lead the way to the summer camp he had rented, sharing with his wife, painter Celia Owen, her son Benjamin Robertson, 14; Alec's friend, actor Rick Wessler, and Rick's friend, Leah. Both women were on errands in Wellfleet when we arrived. Alec said they had promised to return with blueberry muffins for breakfast. Rick was in swim trunks, though the weather was threatening. Alec introduced him as the man who took the photo of Alec on the book's inside flap. The photo also appeared in the New York Times review of July 16th. I complimented Rick on the portrait. In it, Alec is smiling and trusting, most un-cop-like. (In my photos here, Alec looks noticeably older and certainly wary of the photographer. I was suspect to a degree, I suppose. His look seems to say, "All right, who are you?" It's the look you get through the car window just before you're asked to hand over your license.) Midnights reviewers, and the author himself, apologize for how unqualified Alec was for police work at "twenty-three, five months out of college [Bennington], with a degree in music, and without any idea of what to do . . ." In the book, as in person, Alec is quick to point out his shortcomings. Thus disarmed, we go along with it. Surely at 23, with his slender build, delicate hands, and finely chiseled features, he would look more believable on a stage in romantic costume -- a troubadour of the Middle Ages or a bohemian of the [19th] century -- than in a policeman's blue uniform with page boy locks falling from underneath a visored cap. "I remember mostly being scared," he confided. And, who wouldn't be? I remember playing soldier at that age, putting on a gun belt and, so adorned as sergeant-of-the-guard with the weight of a .45 automatic threatening to topple me as I walked, worrying about the drunks, malcontents, and other troublemakers abroad and belligerent in the pitch blackness. With this in mind, I imagine that Alec Wilkinson probably gained much from his year as a cop. He has since published his first novel and now works [in 1982] as a reporter for The New Yorker, the best literary magazine going, both achievements occurring within a few years of the police experience. It is not easy to get published by Random House or get hired by The New Yorker. It is very difficult to write a funny, entertaining novel that reads so easily. But Alec Wilkinson has done it before his 30th birthday. "The traditional thing t do with your year after college was to go to Europe. This was for me, a year of adventure. There was never any question of staying on. I knew I would never make a career out of being a policeman." "It was a lonely year. I couldn't make friends. People I didn't know, but knew who I was, didn't want anything to do with me. "But the people were what made the experience worthwhile. As I said in the book, I never cared much about what I had to do." "I was taking notes and keeping a journal. I would go into the station, particularly when I was on 'midnights,' about 3 or 3:30 in the morning. (It would take me until 2 or 2:30 to get the door checks out of the way, to have taken care of my responsibilities of the shift.) At that point it was all done secretly. Nobody knew it. There was a particularly shrewd young dispatcher who would come over and say, "what are you doing, writing a book?" 'No.' I'd say, 'I'm writing a letter.' Then, when I'd finished my year, I went back and talked to some of the people again. I'm a much better reporter now than I was then. "I hadn't wanted to be a writer. I went to Hackley, a small boarding-school, a wonderful school in Tarrytown, New York. I got what I consider the most important parts of my education there, instead of at Bennington. I had intended to go to law school, although I gave up that idea. Or I was going to save up as much money as I could and pursue music in a serious way. It wasn't until I was eight months or a year into writing this book that I began to realize this is what I was going to do. Not that it dawned on me, but I found that, in the end, I liked writing more than I liked playing music. I gave up one for the other." "Most of the experiences I had weren't funny at the time. I was scared or I was just over-excited. Later, I saw it as funny." "I never thought I could write anything . . . I never imagined you could make money! There was a study that was on the front page of the New York Times last year. It was discovered that the average writer in America had an income of about $4,500. And the only people they considered in the survey were people who had published at least one book! "When my year as a policeman was up, I went to Europe on a one-way ticket and stayed a long time. I was playing music and traveling. After six months I finally decided I was ready to come home and write the book. "Actually, it wasn't my idea to write the book. I would visit my older brother, Stephan, at his home in Cornwall in the Hudson River Valley and I'd tell him stories and he'd say, 'You ought to write a book about this.' " "I wanted the book to read really fast. I didn't want there to be any hitches or want it to be weighty or ponderous. My God, this was rewritten so many times! My parents' basement is full of manila folders and packing crates with things I have changed. A lot of what I had written was stupid. It had to go. "That was brought to my attention by William Maxwell, at The New Yorker, who was kind enough to help me . . . I don't know if he really knew how heavily I was going to rely on him when he first began reading things for me. I would write something and about every two weeks I would go to see him and, unfailingly, the things I was most proud of were the things he would remove. "Mr. Maxwell was, for about 40 years, fiction editor at The New Yorker, and he's been John O'Hara's editor, and J.D. Salinger's, and, on occasion, Eudora Welty's, John Updike's, everyone's. He is, I think, what people think of as the greatest living editor of fiction. Certainly, of short fiction, anyway. "I would constantly be getting into little backwaters -- spending two days perfecting seven lines that I thought were just terrific and were going to startle everyone, and I would bring them to Mr. Maxwell, and he would say, 'You can't say this,' or 'this has to be removed,' or 'you understand that you missed the point here.' And, I would think at first, 'oh, boy,' and grit my teeth, and after I worked with him long enough, I think I began to develop the ability to catch myself first. I began to realize how much he did to improve my writing." "I hope three years from now I'll have a book coming out. I have some ideas but nothing definite. It's hard for me to do a project like a book, it ties me up for so long . . . I don't write too easily. I enjoy it, but it doesn't come easily, it's not something that comes easily." Midnights was published in April of 2000 as a paperback by Ruminator Books with a foreward by William Maxwell. The cover art is different from the Random House edition shown above.

|

publisher for his first book.

publisher for his first book.