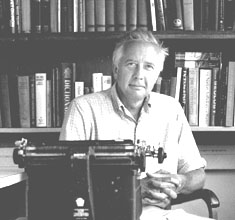

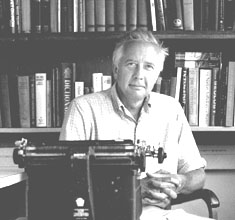

DAVID McCULLOUGH looks the

part and is the embodiment of a successful writer. He lives comfortably

on Martha's Vineyard with his attractive wife, Rosalee, whom

he described in a Commencement Address at Hamilton College just

two years ago as: "The most important person in my life,

my editor-in-chief, my brain trust, my mission control, my first

wife, my present wife..."

He is tall, trim, and charming.

In a tattersall-checked shirt and faded chinos he's more believable

in the role than all the actors who have played the part. Probably

because the writer in this case is real and, as so, unpretentious.

David McCullough is twice a winner of the National Book Award

and of the prestigious Francis Parkman Prize. For his monumental

Truman he  received the Pulitzer

Prize.

received the Pulitzer

Prize.

I spent five hours in the genial

and hospitable company of David and Rosalee McCullough. The interview

produced the proverbial surfeit of riches -- so many profoundly

illuminating observations that they need no exposition. That

which follows is David McCullough, verbatim.

I WORKED FOR TIME-LIFE and then went

to Washington during the Kennedy administration to work for the

USIA when Ed Murrow was at its head. Then I came back to New

York and worked as an editor and writer at American Heritage

for six years. And I was writing, nights and weekends, a book

which turned out to be The Johnstown Flood, which had a wonderful

reception, much more than we expected. It gave me a grub stake

to cut away and try writing full time.

Rosalee and I sold our house in White

Plains and got out, trying to cut costs. We moved first to Middlebury,

Vermont, and loved it. But I found I was really out of touch

up there. This surprises some people who say, "How out of

touch can you be now, living on an island?" What they don't

realize is that I can be in my publisher's office as quickly

as it once took me to get from Wilton, Connecticut, where I was

living and commuting -- by taking the morning flight right out

of the airport, five minutes from here! I actually get to New

York a little too early: they don't open up down there until

9:30 or 10 o'clock, and I have to get a cup of coffee somewhere

and wait for the business day to begin.

Also, there's such a constant flow of

people coming to the Island, not just in the summertime, either,

but on weekends...people who are in work that represents a world

beyond these shores...people who are fun to talk to and who are

stimulating...who keep the brain from turning into a pudding.

We don't see people, except on weekends;

I'm working most of the time. I work very hard. We've made wonderful

friends who don't live on Martha's Vineyard but who come here

in the summer or on weekends. And we've made terrific friends

who live here year-round. The diversity of backgrounds and places

of origin, even in a little town like West Tisbury is extraordinary.

Right up and down this street, the professions that are represented

by retired people, the avocations represented by people doing

independent work of different kinds, is really remarkable.

One of the wildest misconceptions is

that writing is a solitary pursuit. Nonsense. It really isn't!

You have to go see people to do your research; you get to interview

people. You get to meet people who are working at your publishing

house. In my kind of writing, one subject may be engineering,

the next subject may be politics. You get to know all about different

professions, meeting those kinds of people. Not it is not solitary.

Another misconception is that writing

is somehow easy. The hardest thing of all is to make it look

easy. It's like anything else -- a great batter, a great tennis

player -- they make it look easy, but it isn't. The other thing

is that I don't think there's any such thing as a Muse, for example.

It's going out there every day and doing it. That's what it is.

It's working.

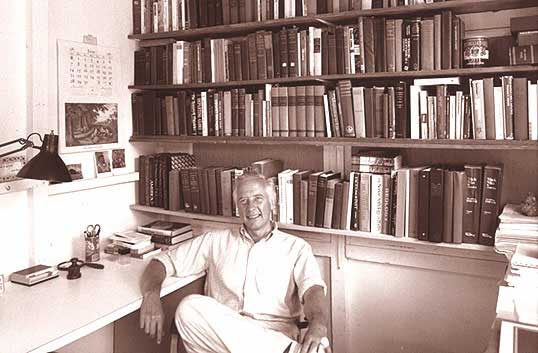

When I'm in my studio I wouldn't rather

be anywhere else in the world. The idea that I can make a living

doing what I'd rather do than anything else, is, to me, just

a miracle. It's a gift that every day I can do that. And when

I think of the unpleasant or seemingly pointless days that other

people spend in their lines of work, I realize how blessed I

am. I have terrific support in Rosalee. I would rather go out

there and work on a book I really want to write than anything

I know.

All of my books are derived out of a

great ignorance. I've never known much about any subject that

I started. When I started it, I didn't know anything about the

Panama Canal. I didn't know anything about the Brooklyn Bridge.

I didn't know anything much about Theodore Roosevelt...certainly

I knew nothing about asthma, absolutely nothing about his mother

and father. And, as I said earlier, if I had known, I don't think

I would have wanted to write the book. It's the discovery; it's

getting on the track; it's the accelerative quality of curiosity.

It's like gravity -- it accelerates...the more you find out,

the more you want to find out, and that's a great time...boy,

it's wonderful!

The real fun of what I do is in doing

it. The reviews are gratifying and sometimes thrilling, the awards,

the wonderful letters from readers...all that is terrific. I

dearly love it and need it, but the real fun is in going out

there and doing it. My favorite book is always the book I'm working

on.

1981

I'm a pretty fast typist. I work on

the typewriter. I compose on the typewriter and that comes from

having worked on magazines. I rewrite. If I can produce two typewritten

pages that I'm satisfied with in a morning, then I'm moving along

just fine. Four in a day. I'm out there all day. In my work it

isn't all writing. I'm reading. I'm checking notes. Mulling.

I do a lot of mulling. Looking up quotations or facts or whatever...it's

not just writing. When I'm really working full out, four good

pages a day is what I aim for.

I rewrite as I go along. I don't write

a first draft, so called, and then rewrite the whole book. I

could never do that. I'm building as I go along. So when the

chapter is finished -- except for later on when I might come

back and edit when it's been retyped -- I feel that's it.

I work from an outline, but I keep revising

it as I go along. I've never gone to a publisher with an outline.

My outline is strictly for me. It's a guide, mainly to show where

you begin and where you end and sort of how it's going to be.

But it's always changing, mainly because it picks up a life of

its own. And you change as you go along. Take a book of my kind,

on which you're spending four years. Well, four years later,

you're not the same person you were four years before. And, more

obviously, your knowledge of the subject has become much deeper:

there's more range and sensitivity to what your mind is able

to grasp in all this. So that, very often, I've had the experience

that when I'm nearing the end of the book, I realize that the

first part -- that I wrote in the beginning -- is not quite the

same tone of voice.

The real insights start to happen for

me after I'm well into it because you begin to make connections

which you didn't make before. You begin to see what you didn't

see then. Conrad said, "Writing is seeing." He was

right. It is. My great feeling is that you have to see a subject

in context. If I have an operational word it's context. I try

to see the story in the context of a lot of things that other

writers on the subject have not bothered with.

A subject like the Panama Canal, let's

say. My effort there was to see that event, that achievement,

in the context of politics, of history, of medicine, the geology

of Central America, the advent of certain technology in the late

nineteenth century which was changing what could be accomplished,

what could be proposed...to see it in the context of our North

American view of Latin America -- all those. Finance -- a French

company went broke; it was the biggest financial collapse in

the history of the world up to that point. So that meant that

I had to know an awful lot about how that came about and why

that was. That same story unleashed the first serious outbreak

of anti-Semitism in France. So I had to understand what that

was all about. It eventually let to the Dreyfus affair.

In the Roosevelt book, I've tried to

see that individual, not just in the context of his family who

were the closest to him and most important to him, but also to

see the family in the context of a particular social class in

which they were prominent. And, then, to see that social class

in the context of New York City, circa 1970 to 1885, 1886, and

so forth. To see their income in the context of the times, for

example. Not to look at those dollar figures that people quote

and say, "That's what it was." You have to ask "What

does it mean in scale?"

I think the training that I had, the

experience I had in drawing and pa inting

has helped me enormously in this work. Because one thing you

do learn about is scale. And proportions. To see events and facts,

if you will, or personalities, in proportion. Teddy Roosevelt

says, "My inheritance meant that I would have an income

of $8,000 a year. That made me comfortable, but not rich."

Every biographer who has ever written about Roosevelt has taken

that statement and just played it back at face value. So I thought,

"Well, what did that mean in his time?" And I found

that what it meant, and it's an astonishing thing to discover,

is that his income was more than that of the president of Harvard,

who earned $5,000.

inting

has helped me enormously in this work. Because one thing you

do learn about is scale. And proportions. To see events and facts,

if you will, or personalities, in proportion. Teddy Roosevelt

says, "My inheritance meant that I would have an income

of $8,000 a year. That made me comfortable, but not rich."

Every biographer who has ever written about Roosevelt has taken

that statement and just played it back at face value. So I thought,

"Well, what did that mean in his time?" And I found

that what it meant, and it's an astonishing thing to discover,

is that his income was more than that of the president of Harvard,

who earned $5,000.

History is the story of people. The

events are the people...unless it's a natural event. Krakatoa

goes off. That really has nothing to do with people except that

it has a lot to do with how people responded to it, how they

felt about it, who got killed, and so forth. Very few professional

historians are, at heart, interested in people. And that's one

of the reasons that so much that is written in the way of history,

and in the teaching of history, is boring. I can't tell you how

many people have come up to me and said, "Oh, if history

had only been taught like that when I was in school, I would

have become a history major."

Well, there isn't any other way to do

it, in my view. That's what history is, and the crucial thing

is to feel, not just to know, but to feel that people of the

past were just as real, just as alive, just as prey to the same

emotions, fears, exhilarations -- whatever -- that we are. And

the only thing that is different is their time was different

from our time, but they didn't think they were living in The

Past.

I want to make a point. I use photography

as a bibliographic source. I study old nineteenth century photos

in order to learn about the past. One of the reasons we feel

people in the old days weren't quite human -- or certainly were

very different from us -- that they weren't bathed in the same

light we're bathed in, that there wasn't air around them the

way there is air around us -- is that they see those old photographs

taken with a certain type of camera which gave that precise clarity,

and you have those people with those somber looks, stiff, and

so forth. If you look at enough of those pictures, you begin

to think those people weren't alive, the way we are alive. The

great antidote, the great cure for that feeling is to go and

look at something like the Pisarro show in Boston and see that

it's a nineteenth century man painting life, painting light,

air, the sense that we're creatures in space...it's the same

as we are now. And I think that maybe the artist may turn out

to be the great historian.

To think that photography is reality

is one of the great hoaxes of our time. Very often, photography

is more of an abstraction than painting. Far more. Those nineteenth

century black-and-white photographs are far more removed from

reality than the paintings of the nineteenth century masters.

I kept a large book of paintings by American impressionists on

my shelf while I was writing the Roosevelt book, and I would

take out that book every so often and just page through to look

at those pictures, just to remind myself of the reality of the

time and of the people. We're all the same. And, of course, one

of the joys of my work is to bring people to life and to make

the reader feel what it was like to have been alive then, to

have part of that.

If you want the facts on some aspect

of history -- whether it is Roosevelt, or whatever -- you can

get that in an encyclopedia. That's not why I write books. I

want you to feel it, to sense the story. I really don't think

of myself as a historian. I don't call myself a historian. I'm

a writer whose milieu, if you will, is the past. And the past,

you know, can be an hour ago.

Photographer unknown, 1998

Photographer unknown, 1998

David McCullough's books include

The Johnstown Flood, The Great Bridge, The Path Between the Seas,

Mornings on Horseback, Brave Companions, and Truman. None of

his books has ever been out of print. In a crowded, productive

career, David McCullough has been an editor, essayist, teacher,

lecturer, and familiar presence on public television, as host

of "The American Experience" and narrator of numerous

documentaries such as "The Civil War." He is president

of the Society of American Historians [though in this earlier

interview he refused to call himself a historian]. He holds twenty-two

honorary degrees and has been elected to the American Academy

of Arts and Sciences. A gifted speaker, he has lectured in all

parts of the country and abroad, as well as at the White House,

as part of the White House presidential lecture series. He is

also one of the few private citizens to be asked to speak before

a joint session of Congress. David McCullough was born in Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania, in 1933. He was educated there and at Yale, where

he graduated with honors in English literature. He is an avid

reader, traveler, landscape painter, and Sunday night spaghetti

chef. He lives in West Tisbury with his wife Rosalee Barnes McCullough.

They have five children and twelve grandchildren. He is currently

at work on a book about the intertwining lives of John and Abigail

Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Critic John Leonard, writing in The

New York Times, said that David McCullough was incapable of writing

a page of bad prose and that "we have no better social historian."

received the Pulitzer

Prize.

received the Pulitzer

Prize.

inting

has helped me enormously in this work. Because one thing you

do learn about is scale. And proportions. To see events and facts,

if you will, or personalities, in proportion. Teddy Roosevelt

says, "My inheritance meant that I would have an income

of $8,000 a year. That made me comfortable, but not rich."

Every biographer who has ever written about Roosevelt has taken

that statement and just played it back at face value. So I thought,

"Well, what did that mean in his time?" And I found

that what it meant, and it's an astonishing thing to discover,

is that his income was more than that of the president of Harvard,

who earned $5,000.

inting

has helped me enormously in this work. Because one thing you

do learn about is scale. And proportions. To see events and facts,

if you will, or personalities, in proportion. Teddy Roosevelt

says, "My inheritance meant that I would have an income

of $8,000 a year. That made me comfortable, but not rich."

Every biographer who has ever written about Roosevelt has taken

that statement and just played it back at face value. So I thought,

"Well, what did that mean in his time?" And I found

that what it meant, and it's an astonishing thing to discover,

is that his income was more than that of the president of Harvard,

who earned $5,000. Photographer unknown, 1998

Photographer unknown, 1998