|

MALCOLM WELLS is impressive. He speaks eloquently in spare sentences. The resonance of his voice is as commanding as his choice of words and delivery: deliberate, restrained, and precise. He is witty and, from time to time, mischievously humorous. He is tall and spare, with the type of masculine good looks Hollywood has not been able to find since Gary Cooper and Spencer Tracy. Had Central Casting seen Malcolm Wells, Charlton Heston would still be a cowboy. Wells would be so much more impressive as The Almighty. As He, Malcolm Wells would put us in our place, which, in his order of things, is just behind weeds. He lists his priorities thus: Not the other way around, which, he laments, is the way it really is in America. He recalls that the first ten or more years of his career as an architect were spent "destroying" forests and farmland for factories, designing such edifices for an industrial giant he prefers not to identify -- "It's not their fault. I did the designing, not they." Mac Wells does not hide his past. He says he specified big heating plants and big cooling plants and confesses to having been paid well to do so. He knows now that he missed the point then of doing "good architecture" -- he was only concentrating on the tricky details, adding a little greenery here and there for decoration. "It was covered with vines and shrubs -- everyone believes it to be a conservationist's building -- they thought I did a great job. It is really bad, and yet I got away with it. It's a pity that most architects can get away with that sort of thing." "The green plant is the life system

on this planet. That is what I believe life is all about. That

is what architecture should be all about. Yet all of us who build

or develop or design or engineer structures do nothing but destroy

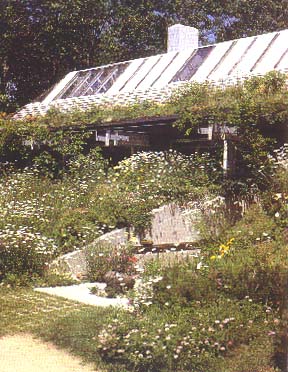

that very life principle." Mac Wells visited the work of Frank Lloyd Wright in Arizona in June of 1960. The day was extremely hot, but the inside of the master's underground theater proved delightfully cool. Wells says, "it made a little light bulb go on in my head." He also visited an underground house in west Texas. "A concrete vault thirteen feet below the earth with a complete Cape Cod cottage in it and plastic flowers in the window boxes and electronic sunsets outside the windows." He was astonished. "I couldn't get out of there fast enough," he says. Obviously, the Texas house is not what Wells means when he says "underground." He believes in sunlight and outdoor exposure. His concept of underground does not mean deep-in-a-hole as in a bomb shelter. The Brewster home he built . . . he

calls a "true earth shelter,' explaining that it impinges

on the environment as little as possible. "Mounding earth

around and over a house," he says, "may be, in a sense,

artificial, but it is far more appropriate than building a conventional

box to stand on what was once living land." Cape Cod's well-drained sandy soil offers ideal conditions for such dwellings. But [the Wells' lot] had a ridge that ran north and south, making it unsuitable for south-facing solar designs he had in mind. Moreover, he wanted to test his ingenuity in designing something with more of a challenge. The design theme of the house became a long, triangular tunnel of glass -- a skylight that capped the entire ridge of the roof. The effect is celestial. Sunlight enters the skylight and is diffused through suspended greenery, verdant foliage above rough-sawn 4 x 12 [-inch] beams. Walls are white, furnishings reflect simple elegance in form and substance. Paintings, sculpture and photography make a smashing picture . . . Mac made much of the furniture: simple raw-wood designs that harmonize with the unfinished concrete walls and buttresses and rough-sawn wood trusses overhead. The large concrete buttresses, floors and walls, are part of a giant thermal mass used to store heat. They also support hundreds of tons of earth on the roof, in which wild grasses and flowers grow. |